Published by: BhumiRaj Timalsina

Published date: 22 Jun 2021

The Uncertainty Principle also called the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, or Indeterminacy Principle, articulated (1927) by the German physicist Werner Heisenberg, that the position and the velocity of an object cannot both be measured exactly, at the same time, even in theory. The very concepts of exact position and exact velocity together, in fact, have no meaning in nature.

Ordinary experience provides no clue of this principle. It is easy to measure both the position and the velocity of, say, an automobile, because the uncertainties implied by this principle for ordinary objects are too small to be observed. The complete rule stipulates that the product of the uncertainties in position and velocity is equal to or greater than a tiny physical quantity, or constant (about 10-34 joule-second, the value of the quantity h (where h is Planck’s constant). Only for the exceedingly small masses of atoms and subatomic particles does the product of the uncertainties become significant.

Any attempt to measure precisely the velocity of a subatomic particle, such as an electron, will knock it about in an unpredictable way, so that a simultaneous measurement of its position has no validity. This result has nothing to do with inadequacies in the measuring instruments, the technique, or the observer; it arises out of the intimate connection in nature between particles and waves in the realm of subatomic dimensions.

Every particle has a wave associated with it; each particle actually exhibits wavelike behavior. The particle is most likely to be found in those places where the undulations of the wave are greatest, or most intense. The more intense the undulations of the associated wave become, however, the more ill-defined becomes the wavelength, which in turn determines the momentum of the particle. So a strictly localized wave has an indeterminate wavelength; its associated particle, while having a definite position, has no certain velocity. A particle-wave having a well-defined wavelength, on the other hand, is spread out; the associated particle, while having a rather precise velocity, maybe almost anywhere. A quite accurate measurement of one observable involves a relatively large uncertainty in the measurement of the other.

The uncertainty principle is alternatively expressed in terms of a particle’s momentum and position. The momentum of a particle is equal to the product of its mass times its velocity. Thus, the product of the uncertainties in the momentum and the position of a particle equals h/(2) or more. The principle applies to other related (conjugate) pairs of observables, such as energy and time: the product of the uncertainty in an energy measurement and the uncertainty in the time interval during which the measurement is made also equals h/(2) or more. The same relation holds, for an unstable atom or nucleus, between the uncertainty in the quantity of energy radiated and the uncertainty in the lifetime of the unstable system as it makes a transition to a more stable state.

The uncertainty principle, developed by W. Heisenberg, is a statement of the effects of wave-particle duality on the properties of subatomic objects. Consider the concept of momentum in the wave-like microscopic world. The momentum of waves is given by its wavelength. A wave packet like a photon or electron is a composite of many waves. Therefore, it must be made of many momentums. But how can an object have much momentum?

Of course, once a measurement of the particle is made, a single momentum is observed. But, like a fuzzy position, momentum before the observation is intrinsically uncertain. This is what is know as the uncertainty principle, that certain quantities, such as position, energy, and time, are unknown, except by probabilities. In its purest form, the uncertainty principle states that accurate knowledge of complementarity pairs is impossible. For example, you can measure the location of an electron, but not its momentum (energy) at the same time.

Picture

A characteristic feature of quantum physics is the principle of complementarity, which “implies the impossibility of any sharp separation between the behavior of atomic objects and the interaction with the measuring instruments which serve to define the conditions under which the phenomena appear.” As a result, “evidence obtained under different experimental conditions cannot be comprehended within a single picture, but must be regarded as complementary in the sense that only the totality of the phenomena exhausts the possible information about the objects.” This interpretation of the meaning of quantum physics, which implied an altered view of the meaning of physical explanation, gradually came to be accepted by the majority of physicists during the 1930’s.

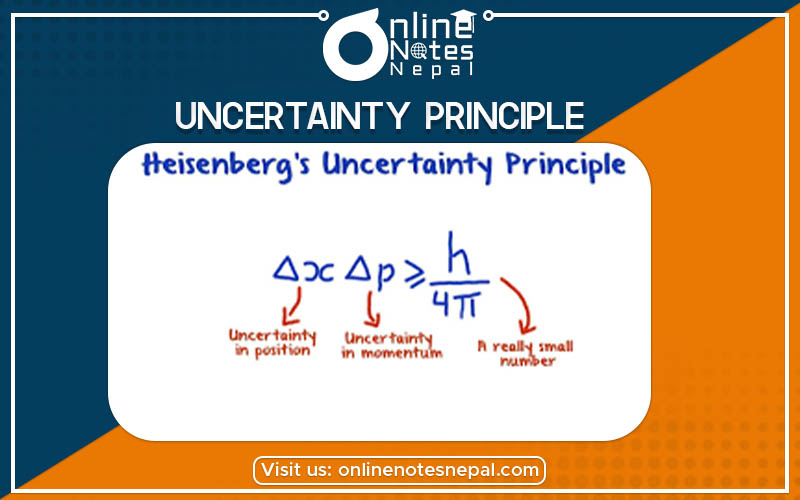

Mathematically we describe the uncertainty principle as the following, where `x’ is position and `p’ is momentum:

Equation

If you liked our content Uncertainty Principle, then please don’t forget to check our other topics Database.