Published by: Sujan

Published date: 14 Jun 2021

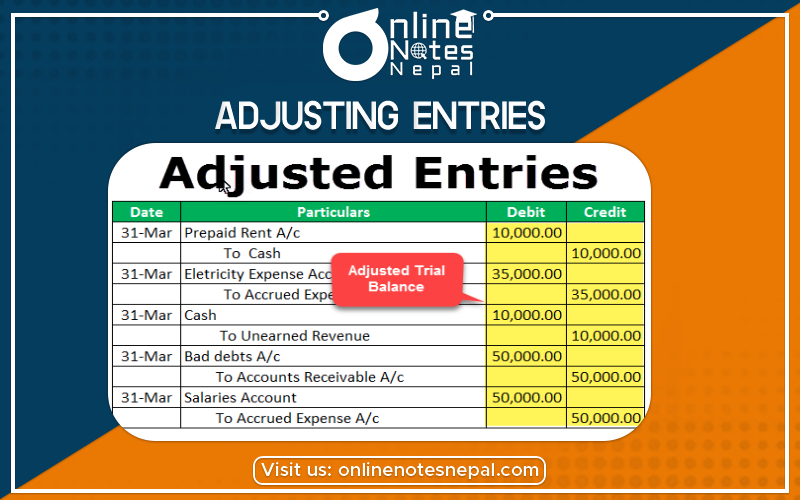

In accounting/accountancy, Adjusting entries journal entries are usually made at the end of an accounting period to allocate income and expenditure to the period in which they actually occurred. Adjusting entries are changes to journal entries you’ve already recorded. Specifically, they make sure that the numbers you have recorded match up to the correct accounting periods. Journal entries track how money moves—how it enters your business, leaves it, and moves between different accounts.

Here’s an example of an adjusting entry: In August, you bill a customer $5,000 for services you performed. They pay you in September. In August, you record that money in accounts receivable – as income, you’re expecting to receive. Then, in September, you record the money as cash deposited in your bank account. To make an adjusting entry, you don’t literally go back and change a journal entry – there’s no eraser or delete key involved. Instead, you make a new entry amending the old one.

When you make an adjusting entry, you’re making sure the activities of your business are recorded accurately in time. If you don’t make adjusting entries, your books will show you paying for expenses before they’re actually incurred, or collecting unearned revenue before you can actually use the money. So, your income and expenses won’t match up, and you won’t be able to accurately track revenue. Your financial statements will be inaccurate—which is bad news since you need financial statements to make informed business decisions and accurately file taxes.

One more thing: Adjusting journal entries is essential for depreciating assets. Which is important for reporting tax deductions and balancing your books.

If you do your own accounting, and you use the accrual system of accounting, you’ll need to make your own adjusting entries. If you do your own accounting and you use the cash basis system, you likely won’t need to make adjusting entries. No matter what type of accounting you use, if you have a bookkeeper, they’ll handle any and all adjusting entries for you.

The five types of adjusting entries

If making adjusting entries is beginning to sound intimidating, don’t worry—there are only five types of adjusting entries, and the differences between them are clear-cut. Here are descriptions of each type, plus example scenarios and how to make the entries.

1. Accrued revenues

When you generate revenue in one accounting period but don’t recognize it until a later period, you need to make an accrued revenue adjustment.

2. Accrued expenses

Once you’ve wrapped your head around accrued revenue, accrued expense adjustments are fairly straightforward. They account for expenses you generated in one period but paid for later.

3. Deferred revenues

If you’re paid in advance by a client, it’s deferred revenue. Even though you’re paid now, you need to make sure the revenue is recorded in the month you perform the service and actually incur the prepaid expenses.

4. Prepaid expenses

Prepaid Expenses work a lot like deferred revenue. Except, in this case, you’re paying for something upfront—then recording the expense for the period it applies to.

5. Depreciation expenses

When you depreciate an asset, you make a single payment for it, but disperse the expense over multiple accounting periods. This is usually done with large purchases, like equipment, vehicles, or buildings.

At the end of an accounting period during which an asset is depreciated, the total accumulated depreciation amount changes on your balance sheet. And each time you pay depreciation, it shows up as an expense on your income statement.

The way you record depreciation on the books depends heavily on which depreciation method you use. It’s a pretty complex operation involving large sums. Considering the amount of cash and tax liability on the line, it’s smart to consult with your accountant before recording any depreciation on the books. To get started, though, check out our guide to small business depreciation.